Before the Biennale: A 2015 conversation with Carlo Ratti

Unearthing an interview from the late-great uncube magazine

The Venice Architecture Biennale opened last week. In my twenties I went to every biennale opening for five years straight, alternating art/architecture/art, and I loved practicing the minor code-switching between the two. There are observable differences between the scenes, although if pressed I’d say it comes down to the fashion (shiny vs black) and how people navigate the vaporetto (with a compass vs without).

Now I usually skip the opening bonanzas (stress, wet feet, bad pizza) and instead if I visit I go at the tail end of the shows, when the reviews are long-since in, when the pieces are on the precipice of being de-installed, when it’s empty enough that you can see the work, and when you can observe how the show has weathered the crowds and opinions. (I feel the same way about waiting to read The Book of the Year—I won’t be reading e.g. Intermezzo or All Fours until the discourse is expired.)

I do miss eating chunks from enormous wheels of parmesan at palazzos, but if I didn’t start going to Venice in the off-season I wouldn’t have learned about e.g. the “cat hospital” (a medieval hospital that is still functioning as a ward but is mostly full of cats) or the last real squat in Venice, where you can get 2-euro wine in a plastic cup, 3-euro pizza from their oven, sit in on an anarchist reading group, and watch live music. Better than trying to spot a single artist among the collectors through a spring drizzle in the Guggenheim courtyard.

2025 is NATURAL and ARTIFICIAL and COLLECTIVE

This year’s arch biennale is curated by Carlo Ratti, an architect-engineer-urbanist-academic and the longtime director of MIT’s Senseable City Lab, which, broadly…. is for studying and changing cities in real time. As in: tightening feedback loops between data collecting and urban planning; designing infrastructures that respond quickly to environmental and social changes; what you might call some kind of handshake between bottom-up and top-down change.

Carlo named the biennale Natural. Artificial. Collective. and in his curatorial brief he foregrounds climate change as The Thing architects should be dealing with. He calls the 750-participant biennale a “living laboratory” (he loves labs) and in addition to his handpicked projects, he ran an open call (unusual) to gather contributions, leading to an enormous range.

Early reviews—god love Olly Wainwright—suggest that much of this is awesome but much is haphazard (“like trying to complete the internet”), that there are a lot of robots, and, like every biennale, it ends up trying to split the difference between showcasing big-name architecture while acknowledging the statecraft of national pavilions (Israel and Russia didn’t open pavilions this year) and the violence underpinning much of what drives the built (or un-built, in the case of bombing) environment. But that’s a feature of biennales, not a bug, and the curatrix does what s/he can. When trying to deal with and portray intangibles and mega systems in physical space, I understand the maximalist approach.

A decade-old interview UNEARTHED

While reading the press, I remembered that I interviewed Carlo Ratti TEN YEARS AGO. Back when I used to be in architecture we had various chats and at one point we did a real interview after I heard him speak at a Berlin digital society conference called re:publica (now in its 25th year).

But where is that interview?! Like so many things we’ve all written, it no longer lives on the internet. I wrote it during my beloved years at the LATE GREAT uncube magazine, which has been taken down by the powers-that-own-the-servers, and who seem to think the negligible web hosting fee is not a worthwhile line item on their budget. We’re still working on resurrecting the archive. You can read an oral history of the four-year project here.

For now, you can experience a stuttering facsimile of the website on the Wayback Machine, although it’s hardly accessible in all its glory: when it launched in 2012 it was a GENUINELY interesting approach to publishing online. It had a glorious handmade design and you could read the issues horizontally, like turning pages, or access them as a vertically scrolling text-only format, and there was a navigable ToC at the bottom of the screen (2012 yall!). We had monthly issues on topics from Pilgrimage to Storage to Death to Communes to Bricks, and we had a brimming blog with some of the best writing responding to that moment in the archiworld.

Berlin!

I sometimes talk about the architecture scene in Berlin in the 2010s as a bounty of CONVERSATION about architecture. Post-2008 crash a lot of very smart designers weren’t able to land (overworked underpaid) jobs in Big Firms and instead flocked to places like Berlin to talk Speculative Praxis and imagine things without stressing about whether someone would pay for them to be built. As much as I became a temporary architecture buff obsessed with Hinrich Baller and Frei Otto and (yes) Adolf Loos, I spent at least as much time in the world of the never-built: arguing about the language we use to talk about the built environment (“International Architecture English”), the future of better cities, the way people actually use existing spaces, the way cheap and temporary interventions can sometimes make a bigger, faster difference than the mega intrusions that end up as landmark icons.

I credit my intro to the world of architecture — and my understanding that architecture is about imaginings, afterlives, ethical questions, political stakes — to my apprenticeship with Berlin legend Lukas Feireiss, a polymath of a curator, writer, teacher. He brought me on to assist with his 2011 curatorial project Testify! The Consequences of Architecture at the Netherlands Architecture Institute, for which we also made a book (including… CARLO). Basically we interviewed people who live in or use the buildings that architects intended to improve their lives: “A skateboarding school in Kabul, a cinema in Jenin, murals in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, a garden in Paris and a museum in Japan — what difference do such projects make to the daily lives of the people who use them?” This was a lucky way to learn about architecture at age 22 years old: calling people and asking them about their spaces.

And it was 2010s BERLIN — there was so much empty space — it was in flux — you couldn’t find a better city to talk about palimpsests and traces of divisions and the pitfalls and potentials of modernism and ways to reuse haunted places — from Tempelhof to Tegel to Teufelsberg. My whole first novel was based around one of those speculative architecture projects that was never meant to be built but lived as a somewhat convincing advertising campaign: The Berg.

uncube made so much sense in that context. We were not publishing press releases about new buildings with staged hi-res pics. Per our EIC Sophie Lovell:

Already the second issue with me at the helm, “Carbon” mortified the publisher: “But where are the buildings?” he said. We were not really interested in buildings. For me, there are many blogs out there saying “This is new building, here is another new building, here is a gallery, here is a villa…” We were at no point competing on that level. uncube was about reading around the subject – important and relevant subjects for contemporary architects.

From the beginning this was about saying to architects: “This is shit you need to know about, it is happening around your profession, around this thing you think you know about.”

The interview

This conversation I had with Carlo Ratti a decade ago is still amazingly relevant, both to architecture “at large” and to the biennale itself. In 2015 he was at the Speculative party with us — advocating for a non-deterministic, participatory model of design that prompts debate and avoids imposing solutions on the people architecture is meant to serve. But he is also an architect and he really believes in building things. I’m curious to consider (other people’s takes on) the 2025 biennale with our 2015 conversation about futurism and “tangibility” in mind.

Young Elvia asked some hard-hitting questions… Is it right to ask individuals to shift to sustainable habits rather than focusing our energy on making e.g. companies change? Why were Coca-Cola and Sony Ericsson sponsoring his projects? (In some ways that’s just the eternal question for architects: Who are your stakeholders?) He had good, architect-y answers: When it comes to “individual, political, or corporate change, we want to do it all together. The only way we can change things is really if we create feedback within society that’s part of the design process itself.” As now, he maintained that the right role of the architect/planner is essentially “neutral.” In the last decade I’ve come to believe that being partisan is actually fine/good/correct.

Here’s the piece on Wayback Machine and here’s the text below.

The Tangible Future: An interview with Carlo Ratti

uncube, June 4, 2015

Architect and engineer Carlo Ratti, who directs the research group Senseable City Lab at MIT, is one of the most influential designers and innovators in architecture and urban design. Elvia Wilk met and talked to him at re:publica 15 in Berlin, Europe’s largest conference on the internet and society, where he presented his latest work.

Elvia

The last time we spoke was four years ago, when I was working on the exhibition Testify! at the NAI in Rotterdam, in which you were included. That exhibition focused on revisiting architecture after it was built to try and create a feedback loop of knowledge to help improve future projects.

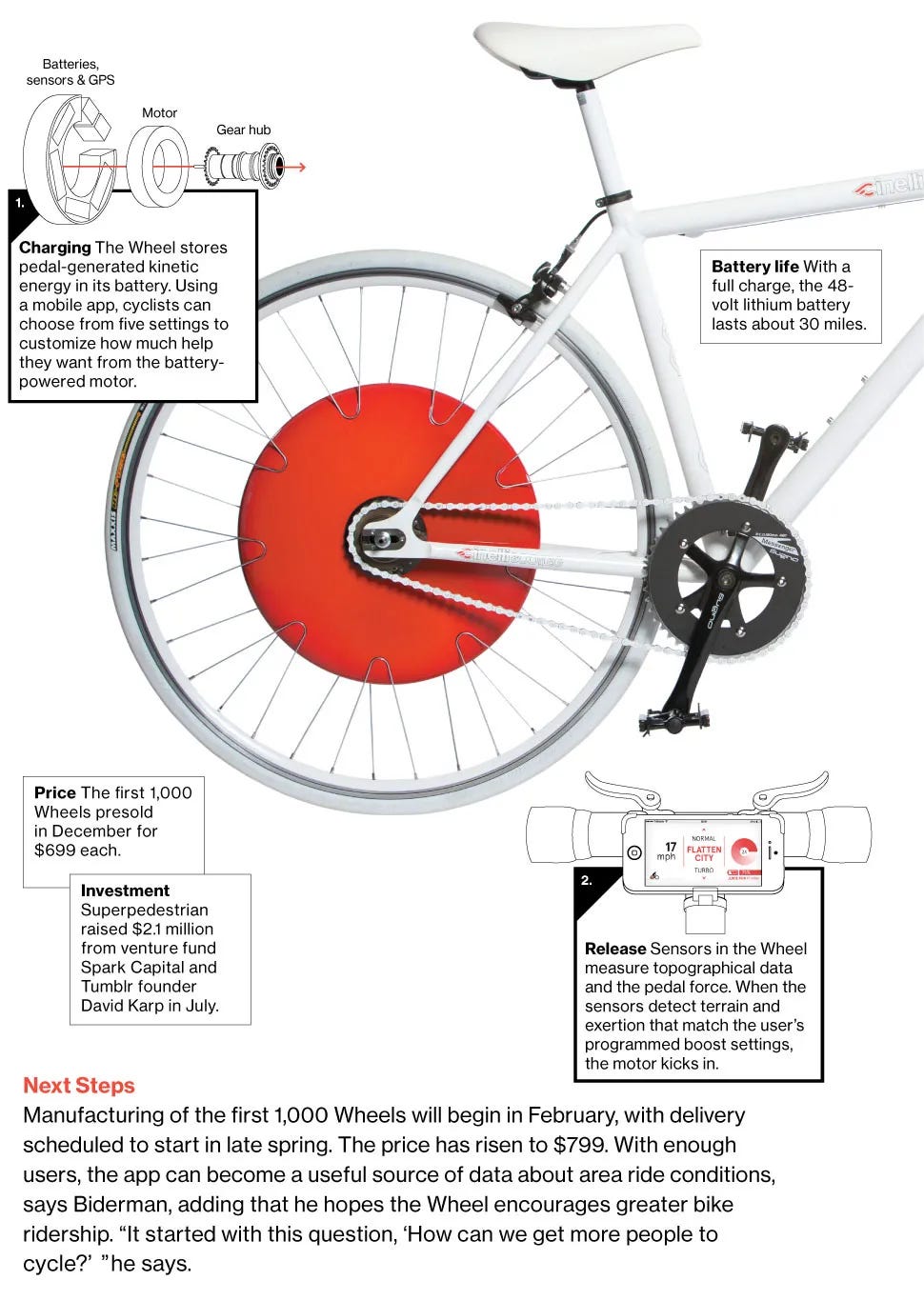

The impression I got then was that Senseable City Lab was aiming to speed up that loop, so that the built environment could respond almost in real-time to information gathered about it, very different from architecture’s traditional slow route. How does time frame play a part in your projects, especially some of the more long-term ones like the Copenhagen Wheel?

Carlo

Copenhagen Wheel has so far taken about five years to reach production phase, which in the automotive industry is a typical time frame between the moment when you show the initial concept and its realisation. In our case it was a learning process, but I’m very happy to see it moving along – online you can see (here) some images of the production line from the factory in Detroit.

Regarding feedback loops, the key point for us is how to create an environment that responds to us better. It’s not just about data collection, it’s about how we can transform the interactions between us. How do we do that? Either by changing behaviour – giving people the ability to change their behaviour – or the environment itself. Transformation is not only about architecture, it’s about changing both sides of the relationship: the human and environmental

.

Elvia

It’s also about the powers that be. Is it right to locate the onus of behavioural change onto the individual, rather than focusing on structural changes, political or corporate, which would be guaranteed to have a wider impact? Your project “Trash Track”, for instance, which uses sensors to track where trash ends up, may encourage people to be more responsible about recycling water bottles – but what about the manufacturers and the recycling industry?

Carlo

You’re totally right, but don’t forget that individuals as activists can put a lot of pressure on the political level and on corporations. I still think that it’s a good way to start. I’ll tell you what we see as our role in the lab or at the office: it’s a little bit like Bucky Fuller’s idea of anticipatory design. The idea is that we can introduce new things, in what we call an “urban demo,” and then people can take a critical approach to what they see. When you do this, you also want to show dystopian things. It’s almost like hacking; you want to show a vulnerability of the system so that we as a society don’t go there.

Elvia

Is that practice something like “design fiction”?

Carlo

In design fiction you probably don’t make it tangible enough. We think it’s very important to introduce artefacts. Let me give you an analogy: evolution. The way natural evolution works is by mutation. Some mutations are more and some less successful. So we ask, can a designer speed up the evolution of the artifical and help to transform the present, so that together as a society we can decide where to go? We want to help show different options for the present, in a good direction but also sometimes in a dystopian direction.

Elvia

Would you distinguish that approach from technological determinism, because it includes an element of structural intervention?

Carlo

Totally. It is deliberately not deterministic, because it starts with human input, introducing new artefacts for people to adopt and increasing the spectrum of possibilities. That goes back to your question about individual, political, or corporate change. We want to do it all together. The only way we can change things is really if we create feedback within society that’s part of the design process itself.

Elvia

As an example about how you work on the individual and on the larger scale, could you talk about one of your major collaborations, such as with Coca Cola or with Sony Ericsson?

Carlo

Thanks for asking that question. In academia you have basically two ways to do research. The traditional way is with governmental support. The difficulty we see there is that between the time you come up with an idea and the time you get the initial results, it may have been years. You start with a proposal, you submit it, maybe a year later you find out it’s approved and you start putting together a team… by that time your initial idea may have changed, but you are locked into the plan. So we are very grateful for the people who support the lab in a way that allows us to explore very fast. This applies to a number of cities and a number of companies. For us the key point is how we can do urban demos the most effectively. The research consortium we have created contains more corporate partners than traditional research does, but it allows us to be more nimble.

Elvia

Does it afford certain sacrifices too?

Carlo

Each of the corporations has its own behaviour in the real world, but the behaviour they all have as part of our consortium is to leave us total freedom in our work. So from this point of view, there is no trade-off in our research.

Elvia

The new issue of uncube is called Commune Revisited. Along the lines of that topic, I’d like to ask if there are any specific outcomes that you want for communal urban living.

Carlo

Wanting a specific outcome in advance is a bit opposite to what I’m saying architects should do. Society responds to mutating technology, and our role as architects should be to introduce new artefacts, contributing to this evolution of the artificial, so that society can respond. For the commons, it’s very important to know the danger of putting “society” first: in that case somebody has made a decision before the technology’s even there. And that decision isn’t part of a debate. Making a plan for society was the role of the architect of the twentieth century, who would say “here is my the solution; now you need to apply it”.

Elvia

Ending up with social engineering.

Carlo

Yes, and it’s top-down. If you really want to create change by engaging people, we believe that you need to be neutral, and you need to make propositions – call it an urban demo, call it whatever you want – and then there has to be a discussion. You don’t want to necessarily say that we should go one way, you also might want to show something that could be potentially dangerous for society. Then you create antibodies together. That’s the only way I believe we can collaboratively decide.

Elvia

So your goal is to create an interface with the public rather than providing a singular vision?

Carlo

It’s about showing very tangible futures, through new technologies or new technological applications, and then allowing open debate about them. If you go the other way around, starting with what you want for society, then you have the twentieth century idea that there’s somebody who has to interpret society and decide the solution alone. It’s like Le Corbusier saying we should turn Paris into a modern city, or demolish everything and build new modernist towns. There are two books that just came out saying basically that Corbusier supported the Fascists. That might have been him in particular, but it was also the general approach.

Watch Carlo Ratti’s whole talk at re:publica

*A fundraiser*

I don’t write much about the solidarity work I do; I believe in people’s privacy and I’m not creating stories, I’m just doing it. But someone I’ve known and supported for five years just got out on parole, and I can’t emphasize how hard it can be for a person to start their whole life over.

Here are the details from the fundraiser site (why is it called Chuffed??):

Our friend William Reddick was granted parole this month, a long-awaited and hard-earned milestone. After a year and a half of re-incarceration, Bill is finally coming home, and we've organized this fundraiser to support him with this huge transition.

The parole board told Bill that he would be released in June or July, but he was suddenly let out on May 5 without warning. He didn't have a chance to prepare himself or to get his post-release plan in place, and he's currently in limbo trying to arrange housing and work.

Bill is a smart, compassionate, and incredibly hardworking person whose journey has included trauma, addiction, and incarceration — but also extraordinary growth. While inside, he earned multiple college degrees and completed several recovery programs. Now, as he steps into freedom, he needs community support.

We’re raising funds to help him cover essentials: food, clothing, transportation, and job-seeking costs.

In his words:

“I was really surprised to be released early. I'm unfortunately in a shelter and struggling to get by. Any help you can provide while I work to reintegrate into society will be greatly appreciated. I want to be successful in my attempt to regain my life as a free person, never returning to prison again. Thank you all.”