My immune system goes on holiday sometimes. When it comes back, it ramps into overdrive, attacking my body and the “invaders” indiscriminately. I’m never sure whether I’m sick or sick, whether I should say I have a cold or a chronic illness, whether my body is underreacting or overreacting. Immune, autoimmune. Fight back, self-destruct. Maybe I’m being taken over—or maybe the call is coming from inside the house. My body, the haunted mansion.

I have plenty of data. The tests come back weird but inconclusive. Too little of this, too much of that. I have no name for the Disease. Just a haywire, unpredictable system and no way to cast blame.

If you don’t have a diagnosis, what do you have? If you’re sporadically sick are you really sick? Are you exaggerating? Are you lying? Where’s the subreddit? (Don’t worry, there’s a subreddit for the undiagnosable.) Doctors will tell you what you have: a psychosomatic issue, which they mean in the all-in-your-head crazy woman way, not in the sense of what the word really means, which is of the mind and the body, where thought and experience and cellular performance are connected and mutually causal.

Anyway. I wrote a novel about all that called A DIAGNOSIS that you can read next year.

By now I’ve come out the other side of the diagnostic machine and my treatment is Pragmatism. I have meds and routines. I go to doctors in dire situations. I read research studies. I do sporadic off-label experiments. When I’m feeling fine, I gaslight myself into thinking that I made it all up (crazy woman), so that when the inevitable relapse hits I’m surprised and indignant and I insist that it’s not happening.

Last week I arrived at that predictable point in the cycle where brute force is no longer working to get through Normal Life, and instead you just have to just Lie Down and wait.

The Lying Down period is the cul-de-sac of chronic illness. You pull in, let the engine idle, then reluctantly shift the gear into park. You wonder whether you will ever pull out this time, or whether this is now a dead end. You may have arrived at the cul-de-sac because you didn’t do a LITTLE Lie Down soon enough and you have been stealing energy from yourself for too long, and you now have no choice but to do a BIG Lie Down. (You know all about pacing and you didn’t pace yourself, so it’s a little bit your fault. But how can you commit to pacing if you don’t have a diagnosis?)

You were not pacing yourself because you believed that all those things you were doing (job, friends, art) were the things that constituted real life—but REAL life, you now remember, is what has been waiting for you all along: your bed. You did not escape it. This is the real you. The active person pretending to be the real you is now revealed to be the fake person. You hate her. You ate her! And now you have to Lie Down.

Luckily while you are Lying Down you don’t have to write the canonical text on your experience of an unreliable body because Johanna Hedva has already written Sick Woman Theory about why your body is attacking itself rather than producing masterpieces or revolutions, and you quote Hedva back to yourself as you let your head drop onto the pillow: You cannot throw a brick through the window of a bank if you can’t get out of bed. You reproach your former un-sick self for not throwing bricks through bank windows while she had the energy, but now it’s too late.

You roll onto your side. Maybe you pick up a book, but more likely, you turn on the home renovation show The Flip Off, about two divorced house flippers who are now competing against each other to profit from the highest ROI on a house flip in Southern California. Marble backsplash, you hear. Two-and-a-half baths. Here there is no critique. Here there is no art. Here there is only passive consumption. You close your eyes halfway. You enter the cul-de-sac.

The April Lie Down

It’s a waste of time to see a doctor if I have the energy to do anything else. But last Wednesday I gave up, and in a subdued rage, gasping for air like a fish halfway evolved for life on land, I busted through the doors of CityMD and asked for a chest X-ray.

The CityMD doctor and I made some jokes about how bad radiation is for us, and then he said the X-ray showed that “infiltrates” had “infiltrated” my lungs. Are they really called INFILTRATES? Yes, Sontag’s military metaphor is going strong. The infiltrates, he said, meant that I had pneumonia and needed a triple course of antibiotics and steroids.

But later in the afternoon, before the Rx arrived, CityMD DMed my patient portal and said Woopsy! A mixup. There were no infiltrates after all. X-ray clear. I was fine.

Okay. The next day I went to the expensive doctor who I resort to sometimes when edging desperation. He said that it wasn’t pneumonia, but that my lungs were fucked up enough to resemble “smoker’s lungs” (smoking is the only thing I don’t do) and he would try to find out why I couldn’t breathe. (He hasn’t found out.) He asked his nurse to take several tubes and bottles of blood to test for all kinds of pathogens ($300 appointment; $75 tests).

Then he asked, as he does every session, whether I had listened to the latest episode of his “viral” podcast. Viral. Heh. I went from his office to take a nap in a movie theater and then to an opening and got home at midnight, fever still 101. No diagnosis, no problem.

The next morning, Quest Diagnostics DMed my patient portal and said that all the blood the podcast doctor had sent them was not viable because the blood had arrived in contaminated and expired containers. Okay. I walked to the Quest Diagnostics nearest my house with a printout of the test requisition, where they took another $75 worth of blood that also cost me a vein. (What futile dogged belief spurs one to do these things out of obligation or duty to an imagined ideal of science? No lab, no doctor, has ever stopped the cycle of Lie Downs. Also, breaking news: Quest Diagnostics just sent 5,000 people to jail due to false positive testing.)

Thing was, I still couldn’t breathe. I decided to try a new person, a pulmonologist, because pulmonologist name comes from the Greek for “lung specialist.” Big mistake! The pulmonologist said that my illness was “too acute” for her to address. She only deals with “real chronic conditions,” not people who just have a cold. Bye bye. Co-pay please.

The fake diagnostic cycle was over. Infiltrated or not, I was on my own. Saturday, I accepted that the curtains had come down on the Theater of Healthy and that the only choice was a real Lie Down. (Maybe they had taken TOO much of my blood and drained me of my last life force??) Instead of going to the teach-in, the memorial gathering, the book launch, the opening, and—I’m forgetting something—I puffed an inhaler four times, then lay down and read a Gothic novel. I didn’t get up for eight hours until I had finished the book.

Manderley

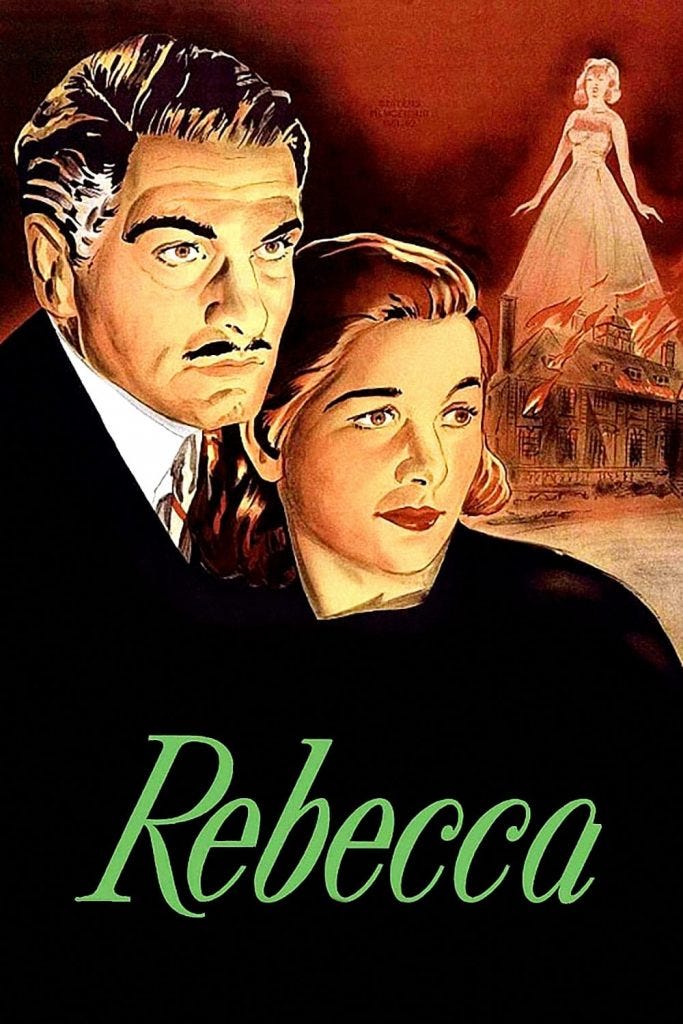

I thought I’d already read Daphne du Maurier’s 1938 Rebecca because I knew the first line by heart: “Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again.” But I guess just knew the line because it’s very famous, and maybe I knew the story because I’ve seen the Hitchcock adaptation and because I’ve read Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights and any number of Gothic novels that it’s sort of like.

The experience of reading Rebecca is so intensely pleasurable exactly because it’s sort of like so many other books. It fits neatly into the grooves of the familiar, but, like all good genre fiction, it’s genuinely stranger than the clichés it trades in.

A poor, naive, 21-year old orphan marries a dashing, rich, middle-aged man whom she meets in a hotel in Monte Carlo. When he brings her back to his enormous Cornwall seaside mansion she discovers that it’s haunted by the memory of his first wife, Rebecca: gorgeous, lascivious, outwardly magnetic and kind but secretly evil and psychopathic. The timid young bride walks in her predecessor’s footsteps, unable to compete with the servants’ and townspeople’s memories of the ravishing Rebecca, whose devoted elderly servant, Mrs. Danvers, will do anything to sabotage who she sees as the new impostor.

A haunted English manor. An evil doppelgänger. A beautiful psychopath. A sinister servant. A crime of passion. Some kind of sexually inflected shame. The book is archetypically Gothic and probably feels familiar to everyone who picks it up. Du Maurier was accused TWICE by TWO different authors of plagiarism. I doubt she actually ripped it; she probably snatched the readymade archetypes out of the air and indulged them, and when you indulge an archetype fully you allow it to get fully idiosyncratic and weird.

It’s like BDM recently wrote about people claiming to be “the first” in any genre:

“Arguments about somebody’s critical or historical position—who is first, who is forgotten, who is overrated, who is underrated, who is influential, who is a curiosity—similarly feel like ways to try to make things into an objective question of numbers instead of embracing the ways in which works of art are both singular and interrelated.”

That doesn’t cover actual plagiarism, but when it comes to writing a genre book, the recognizable tropes are exactly what you’re trading in and playing with. Genre fiction is variations on a theme. Genre fiction is recombinant. You’ve read it but you haven’t. You’ve already dreamt of Manderley.

Malevolent plants

One special freakiness of Rebecca is that it’s dominated by tremendous, terrifyingly fragrant and lifelike plants. The “violent,” “blood-red” rhododendrons are “luscious and fantastic,” the “great branches” of pungent lilac freak her out, the towering lupins overtake the living room, the five-foot delphiniums are too big to cut for vases.

Before he even takes her Manderley, the narrator’s new husband tells her all about the rhododendrons there, as if they’re family members that he wants her to meet. When she gets to Cornwall, in scene after scene she’s diminished, cowed, by the scary splendor of the forest leading to the ocean, the abundant rose garden, the raging blossoms flanking the driveway. Rebecca’s lingering perfume mingles with the fragrance of crushed petals—but as much as the other woman is haunting the scene, the plants are stalking this girl. Just look at these pernicious, lusty, violent, uncivilized creatures:

The rhododendrons stood fifty feet high, twisted and entwined with bracken, and they had entered into alien marriage with a host of nameless shrubs, poor, bastard things that clung about their roots as though conscious of their spurious origin. A lilac had mated with a copper beech, and to bind them yet more closely to one another the malevolent ivy, always an enemy to grace, had thrown her tendrils about the pair and made them prisoners. Ivy held prior place in this lost garden, the long strands crept across the lawns, and soon would encroach upon the house itself. There was another plant too, some half-breed from the woods, whose seed had been scattered long ago beneath the trees and then forgotten, and now, marching in unison with the ivy, thrust its ugly form like a giant rhubarb towards the soft grass where the daffodils had blown.

Alien marriage! Malevolent ivy! Prisoners! Half-breed! The whole dark family drama is embodied by whatever’s happening in the gardens. A good portion of the book is tangled up in this sort of exciting description. (I would have written about Rebecca in Death by Landscape if I had read it before. It’s perfect plant/woman horror.)

Gothic woman theory

In terms of human action, Rebecca has a lot of dead time. For whole chapters, the narrator is nervously lying around on a divan, paranoiacally observing the garden, sneaking around the house hiding from the spooky maid, or standing in the forest fixating on those infernal rhododendrons. Almost like she’s… having a Lie Down. Dozens of tense pages pass full of foreboding hints. Then, suddenly the action happens in dense scenes, which usually include long monologues by one of the main characters in which they reveal a lot of shocking backstory all at once.

So the experience of reading is: lying around in a pool of dread, totally helpless, and then suddenly there’s a torrential downpour of salacious info. At Manderley, you tell yourself that nothing is happening, but dastardly plots, cunning tricks, and deadly revenges are going on behind the curtains. The whole time the narrator is completely passive, aghast, queasy, and frail, letting calamities befall her. At Manderley, you are definitely a crazy woman, but the woman who lived there before you was even crazier. Even the house is psychosomatically ill.

Rebecca is the femme fatale… the narrator is just the femme malade.

Rebecca is perfect sick lit. It is the right book for a Lie Down in the cul-de-sac. You haunt yourself when you’re sick. The half-dead but somehow more-alive doppelgänger… The real person, the living person, is shadowed by the other person… the half-alive person you’re married to in body… the real wife, the false wife, the dead wife… your active self, your passive self… which is the real one? When you resurrect yourself after your Lie Down, who will you return as? Life is still happening while you’re half-asleep on the fainting couch. There will be intrigues when you return.

At the end of my Lie Down I immediately fell asleep for twelve hours. That night I dreamt of Manderley.

"sick lit" J'adore.