I wrote my first book when I was 21. There are probably 100 copies still in existence; please don’t try to find one. It was self-published by a print-on-demand service, back when those were becoming a thing, and I printed it as a “reward” for people who donated to a Kickstarter project, back when Kickstarter was still in Beta. The fundraiser was for a project that the book was about: a month-long roadtrip that might be the most Bard College thing you’ve ever heard about. On our Kickstarter page and blog, my two friends and I called our roadtrip-research-art-project Insiders Out: Exploring Outsider Art in America.

As promised, I went to the amazing Outsider Art Fair in Manhattan last weekend, and while I was starting to write about what is going on with outsider art today, I remembered that I had spent thousands of words trying to answer that question fifteen years ago. I dug out a PDF of my lil book from 2010 and was alarmed to find myself interested in… my younger self?? (Is this how people start writing memoirs?) The book is a time capsule, both because I was a baby then and because there have been huge transformations in the world of outsider art in the intervening years—BUT everything comes back around, and I found a lot of my interviews and notes from 2010 to be weirdly relevant today.

OK SO HOW IS IT RELEVANT

The Contemporary Art economy is propped up by toothpicks and superglue, and it continues to rely on new kinds of things that are not Contemporary Art to keep it together. You need to have an outside to have an inside, and the inside is always leeching off the outside to keep itself animated (and sellable). Of course, there are several insides—there are multiple overlapping art worlds, which collide and reinforce and undermine each other in different ways. That makes the definition of the Outside ever shakier—and actually, even more important.

There’s a lot being said about how contemporary art is extra boring right now (one theory is that artists are pandering to the woke-police in their heads; another seemingly more obvious one is, uh, wealth stratification), and yeah, if boring art is the only kind of art you make or look at, that means the Elite Capture of your politics and selfhood was successful and your attention was distracted (mine sure was), and now you should go look at something else instead. If one art world is boring, you can find another one. Outsiders are constantly getting edged out—so you can go to the edges and redefine them as centers. The problem is that elites tend to find ways to capture the non-boring art at the edges too—and to capture the margins for profit, without materially changing the reality of marginalization. Christina Catherine Martinez wrote in a great recent post: “some people really are drinking the kool-aid, believing that art institutions can spoon a glob of justice into the bowls of the marginalized. Some just want to maneuver whatever tide keeps them in travertine bathrooms, bent over the powdered ends of keys.”

Although by now I have seen many art worlds, I have also been to many Art Basels and I don’t underestimate the power of the monolith. Revisiting the designated insider/outsider thing shows what’s at stake when identity gets coopted for profit, which is that material conditions get erased and people revert to some idea about primitivity/purity, and then start to believe in the existence of some kind of primitive-within-the-sophisticate. Dispossession is the job and the aim of the monolith. I think it makes sense to start from that premise when assessing the state of the art, inside or outside, boring or not.1

Enough! Blogs do not need to be Timely and Urgent. Here is the story of my road trip, a historical discursus on Outsider Art, and a review of the Outsider Art Fair, which, in all its problematic glory, rules. I’ll let Young Elvia talk now.

ART MAJOR

During senior year, two friends and I were trying to decide where to move after graduation, and it wasn’t going to be New York. I didn’t remember this animating anecdote until re-reading said self-published book, but apparently NYer writer Andrea K. Scott (hi!) had come to visit our graduating studio class and someone had asked her whether you needed to move to NYC to be an artist. She replied (per my diary) that if being an artist is what you definitely wanted, then yes, you might want to move to New York for a while. (Someone else asked her if it was a bad idea to sell your paintings at a cafe… I hate to think of how I’d answer a student who asked me that today.)

I was ambivalent about being an artist and averse to the idea of elbowing my way into a Bushwick studio or a gallerina internship. I’d spent a semester abroad at art school in São Paulo un-learning the Western canon. And I was contrarian and didn’t want to do the obvious thing. (In the end, I tricked myself into doing the even more obvious thing and moved to Friedrichshain, made art in Berlin for a year, then turned into an art writer. And now I live in New York.)

I was extra confused about what a “career” should look like because my studio art thesis adviser had some theories about art coming from a pure place uninformed and unburdened by things like history or politics—and luckily if your art came from that pure place, you would be rewarded by the city galleries she took us to—and she was annoyed by my inquiry into things like process-based art and institutional critique, to the point that she said she would only advise me if I promised not to read for my final semester of college so that I could be less cerebral and access my real creativity. This sounded wrong yet appealed to me because I was mentally ill and did believe that thinking was my enemy, which perhaps I could defeat through obsessive doodling and building deranged sculptures out of drywall. (Anyway, I had other finals to pass that required reading, making feigned illiteracy kind of impossible; she gave up and handed me to someone else.)

I learned a lot about color fields, depth, balance, weight, movement, and negative space from that adviser; I do love those things and think that those are things that art is for. But the parallel lesson that selling colors and shapes in Chelsea was the horizon of artistic creation and conversation turned out to be the more meaningful pedagogy, in that it made me reactionary.

I and my artist pal, Elena, were swayed by another senior-year visitor: Drive-By Press, a portable woodblock printing venture started by artists Greg Nanney and Joseph Velasquez, who toured college campuses and art venues, teaching and selling prints. The guys did not live in New York. The guys were having fun. The guys were making enough money for gas. Young Me wrote: “Five minutes into their visit Elena and I had arrived at the same conclusion: a post-grad road trip was not only possible but necessary. It was as if we had just needed to know that someone else had done it, that there were ways of existing outside of the art infrastructures we knew about.” (Aww!)

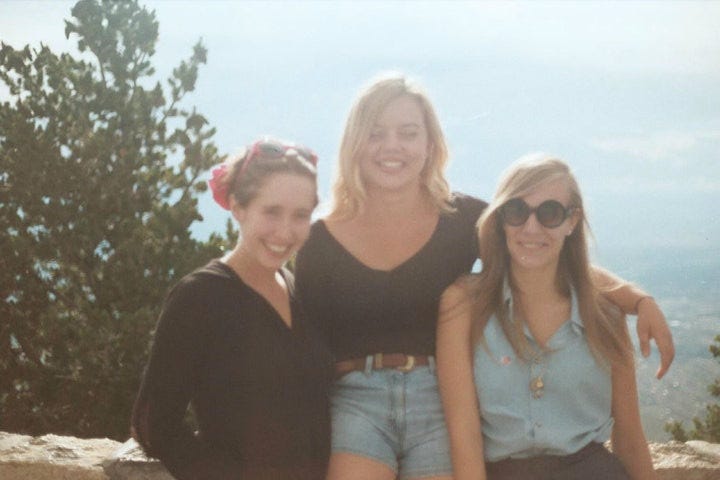

We gathered our friend Alisa for the road show. Alisa had taken an art history class on outsider art and we’d been obsessed by the syllabus, which included no artists I’d ever heard of, many of whom had made enormous installations in remote areas of the US South. We wanted to go see them. We jammed these ideas together under the umbrella of a “research trip”—a term I suggest you use for any Eat Pray Journey in your life—made a map, and started emailing people across the country asking whether we could come visit them. My earnest explanation:

We have decided to travel across the states, investigating how art lives in and forms communities, and exploring ways that our own artistic pursuits can be relevant and alive in America. Fully realizing the ambiguity of categories like “outsider,” we will attempt to learn about how people manage to create art without resources, and answer questions like, how does art function outside of an urban or “art-world” context? How do arts organizations and groups in remote places make art a possibility for everyone? What does it mean for us to be tourists in our own country? How much do we really know about being insiders or outsiders in America?

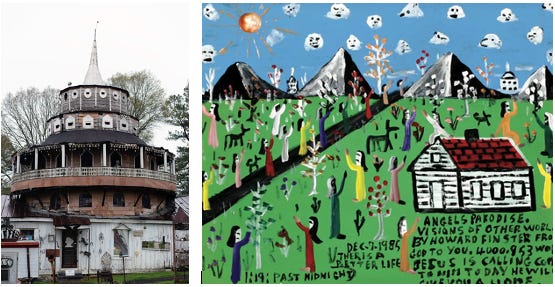

In July we packed up my 97 Honda CR-V and started a loop around the southern half of the country. “The aim was to research marginalized areas of American art. We hoped to learn about the ways in which practices labeled, among other names, Outsider Art and Folk Art have been commodified and categorized.” Because they’re making work out there in supposed obscurity, outsider art is often a destination. The landscape is dotted with sculpture gardens, house museums, trailers full of curiosities, and self-made utopias at the end of dirt roads. We saw the meccas: Howard Finster’s Vision House Museum & Paradise Garden (melancholy reliquary of a brilliant mind), Pearl Fryar’s Topiary (paradisiacal delight), W.C. Rice’s Cross Garden (as wonderfully creepy as it gets), S.P. Dinsmoor’s Garden of Eden (gargoyles?), Henry L. Warren's Shangri-La (mini village, max whimsy).

At the time, several well-known so-called outsiders were still alive and building these worlds. We found out about them in library books, via emails from historians and collectors, and Google roadside attraction reviews. They were all ailing, elderly men. There’s a lot to say about this, and why it took so long for womens “craft” to enter the outsider canon/circuit, which I can write about later if you want. The great hits: Clyde Jones’s Critter Crossing (he gave us a painted critter), Vollis Simpson’s Whirligig Park (“an extremely difficult interview ensued”), John Preble’s Mystery House, Charles Smith’s Art Environment.

The twentieth-century narrative of the US outsider artist is pretty consistent and goes like this: artist with no formal education, knowledge of art history, or contact with contemporary art labors in obscurity; a visionary collector or curator discovers them; their work is brought into the public, sometimes meets with skepticism, but is eventually recognized as a work of genius and graces the walls of the great museums. The artwork is folded into the art market and art history in conflicting ways. I wrote in my little book: “The community must be labeled as marginal to be brought to light, but in doing so, they are made to stay marginal.”

My big fascination was the enduring tension in what happens when the outsider is brought inside: if their work starts to get sold at MoMA, an outsider can no longer be credibly called immune to the art market in which they are now imbricated. One curator told us: There won’t be any American Outsiders left in a generation, because people have too much access to the internet and everybody knows how to read. She said this as if it were a tragedy.

Here is what Young Self says about the artists we met, who were supposed to be unaware that they were making art for an audience:

The artists themselves are not the ones who deny their own “accountability” and “answerability” to the standards of contemporary art. It is their discoverers, their dealers, the people who take it upon themselves to argue for the supremacy of untainted art, who claim that the work cannot be scrutinized by ‘conventional’ standards. The claim is not necessarily that the work cannot stand up to difficult standards, but that it is somehow “beyond” reason and convention. This may be true, but it’s also true that so much Outsider Art, labeled as such through no [desire] of the artist does rigorously engage culturally relevant ideas, making no claim on its own of being innocent or unaware. This work isn't naive at all—it is complex, often ironic, and completely accountable for itself.

Next I try my hand at art theory:

Contemporaneity allows history to be forgotten in favor of the fetish of the new. Art, like fashion, re-invents itself, periodically recycling trends and concepts and framing them as brand-new. This helps explain the fact that Outsider Art has surfaced and re-surfaced at intervals… the Outsider is routinely incorporated into the contemporary. Does this indicate a breakdown of all categorization? Probably not. The future is predictable.

Yes! & no!

QUICK DETOUR

To find out how the artists’ work was contextualized and talked about, we mapped in big museums like Baltimore’s American Visionary Art Museum, small collections like Marcia Weber’s Art Objects in Wetumpka, Alabama, and schools like the Appalachian Center for Craft in Smithville, Tennessee. We visited Drive By Press and other ad hoc / DIY makers and spaces, and we did trades and made money by teaching workshops in things like bookbinding (which we did not know how to do) and Elena silkscreened T-shirts in the back of the car and Alisa made a sound art album… THE HUBRIS. We ended up at the annual Wassaic Project festival in upstate NY, where we showed everything we had made.

Thrown in with the “creative and intellectual pursuits” were the Roadtrip classics, incl. worthwhile roadside attractions—Dinosaur Kingdom (sculptures of the Union army being eaten by dinosaurs), The World’s Largest Collection of the World’s Smallest Versions of the World’s Largest Things, the Precious Moments Museum (the Sistine Chapel, but make it doe-eyed and terrifying). We camped, slept in the car, smoked cigarettes out the window, listened to thousands of hours of [I don’t know, Vampire Weekend??] from the iPod, saw the Grand Canyon. We learned to shoot guns on a range in rural Texas.

The day we visited the world’s largest Treehouse (now sadly burned down) and met its creator, Minister Horace Burgess, in Tennessee, we locked ourselves out of our car and ended up drinking moonshine with some locals and sleeping in a tent on a floating platform in the lake. We sang Thong Song on a stage somewhere in Austin or New Orleans… one Kickstarter reward we offered was recording videos of song requests.

OUTSIDER ART HISTORY 101

The concept of Outsider Art is the product of Modern Art in its various searches to define genius, originality, and elevate high art over the vernacular. To do so, it had to find ways to delineate what was not Modern Art, while also reifying it, stealing from it, and stealing it. You could write the history (many have) of European Modernism as the encounter with and appropriation of a supposed uncultured, timeless, obscure, uneducated “primitive.” You’ll think of Gaugin picking up inspiration in Tahiti and then “filtering his exotic raw material into refined forms” (in the words of OA maverick Roger Cardinal)2, or the moment in 1907 when Picasso laid eyes on his first African mask at the Paris Ethnographic Museum.

Early and mid-century artists were legitimately awed by work not made by the European avant-garde and began to gather it and chronicle its creation. French artist/curator Jean Dubuffet created the term Art Brut (naïve art) to describe his collection of non-professional art, much of it made by “psychotics” and gathered from mental asylums. He opened a foundation in 1948 for this collection (it’s incredible) of “works produced by persons unscathed by artistic culture, where mimicry plays little or no part (contrary to the activities of intellectuals).”

The work would never be preserved or seen without this kind of custodianship; on the other hand, once it was called marginal it could never shake off the label. Throughout the century, people kept discovering new “outsides” and then putting them on show, laundering them through the legitimacy afforded by the art market. The story of OA is in many ways the story of its re-marginalization and cooption. Historian Darby English: “the outlier…that came into being during the historical development of Modernism…now needs to be repeated each time individuals are initiated into the narratives of that development.”3

They Taught Themselves: American Primitive Painters of the 20th Century by Sidney Janis, 1942, aimed to defend “the validity of this expression” and described his pseudo-ethnographic escapades discovering artists who didn’t know they were making art. “Here are stories of how many of the painters were found, of the thrills and experiences of discovery, and episodes revealing the phenomenon of the creative impulse as it grows and thrives in obscurity.” (So what happened when he yanked them out of obscurity into the light? Did their creative impulse die? Did they get paid?)

In the 70s British art historian Roger Cardinal attempted to survey and comprehensively define the field. This intertwined with other museological, scholarly, and activist histories, such as a resurgence of attention to Folk Art in America a little later. In his 1972 Outsider Art, Cardinal explains that he was driven by an interest in “the primitive, indeed the savage qualities that make for art that is not subservient to the cultural norm.” You see all the classic assumptions, for instance, that there is such a thing as one cultural norm, that people working outside that norm are uncultured savages, etcetera. I don’t need to spell it out. The gist is the insistence that the art-makers themselves are “not…the primary seers and knowers of their work,” per Darby English. You need an external arbiter to decide whether (and when and how and where) it’s art and to evaluate it as such. And you need to keep it exotic, while deculturing it so it fits on a wall. A big job for a big curator.

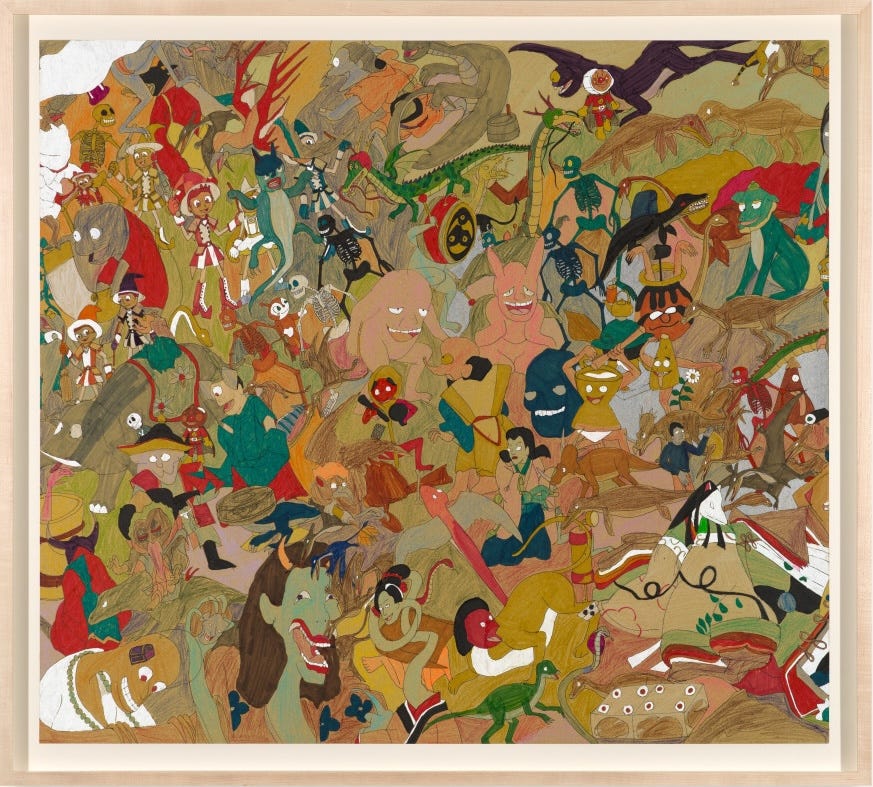

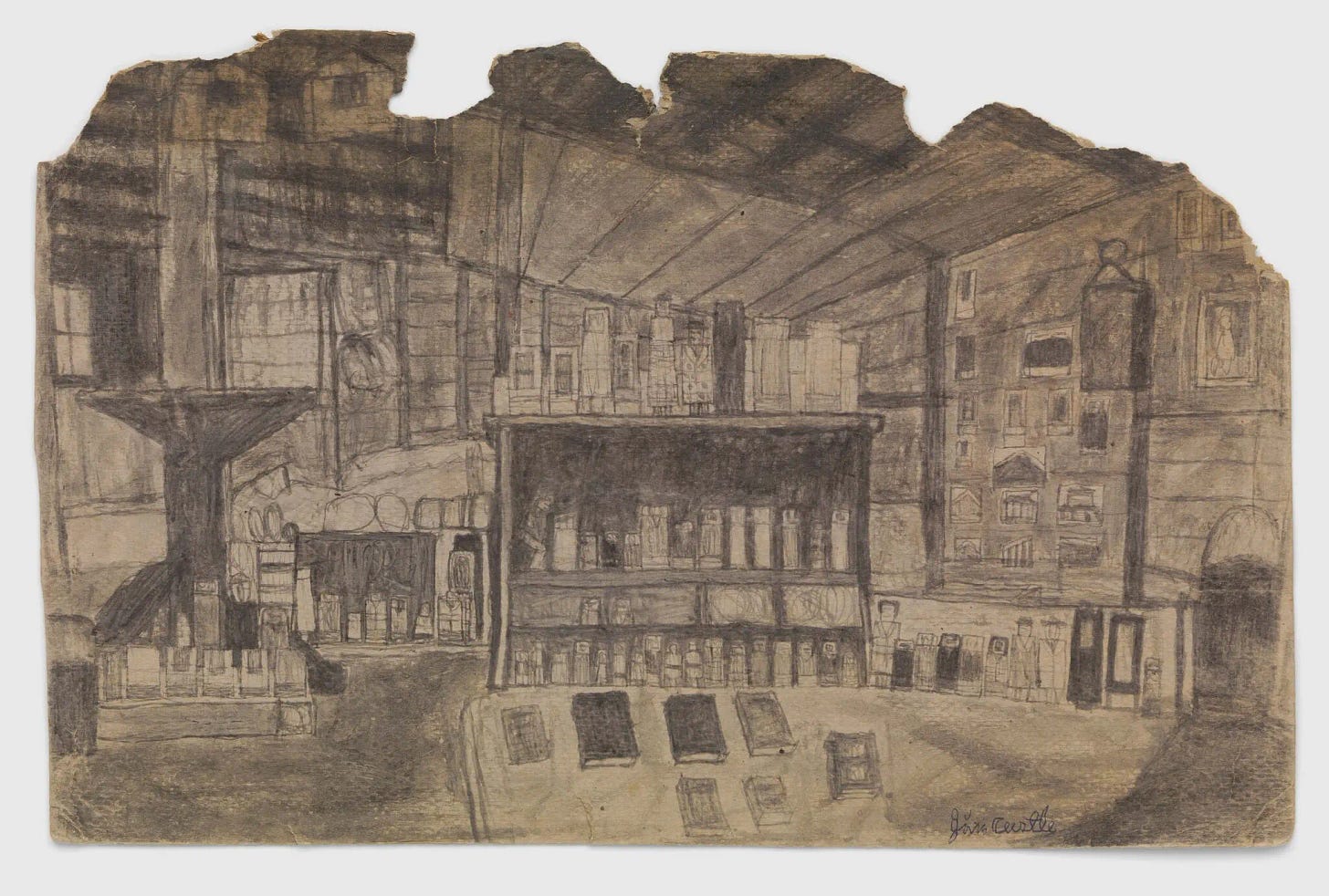

To some extent OA has its own history now and simply means another canon twinned with Modernism that’s been built and reinforced over a century. You’d be hard pressed to find a US outsider show that doesn’t include the Big Ones: Henry Darger, famed recluse and author of 15,000 pages of illustrations of the adventures of hermaphroditic children; James Castle, who grew up deaf in 1920s Alabama and drew on whatever he could find using materials like spit and ash; Martín Ramirez, who created hundreds of meticulous line drawings while incarcerated in a mental hospital; and one of my favorite artists, Bill Traylor, who was born into slavery in 1853 and began painting in his 80s. (Show me a better compositional use of the edge of the page.)

Those are the stories you read on the wall labels, because the stories are marketed along with their art, with the hardship seen as constitutive of the work and essential to understanding it. The artist bio here, arguably, carries more heft than in any other context. Nobody tries separate the art from the outsider artist. A thing about Outsider as Identity: in place of education or pedigree, the Outsider is often “qualified” or their genius “explained” due to an emphasis on their unusual biography or their degree of obstacles in life. You wind up risking being inclusive by making people identical with their identity categories, leaning on their pain or circumstance as the fount of their creativity, and sometimes overriding real aesthetic engagement through obsession about all they’ve been through. So you can probably see where that goes when it comes to… yet again, ELITE CAPTURE. We do not want to make trauma the condition for doing [anything much less] virtuosic art.

OA has been brilliantly reconceived and reframed through a few notable curatorial opuses—my favorite was Lynne Cooke’s exhibition Outliers and American Vanguard Art at Washington’s National Gallery in 2018, which did not make hierarchical or pedagogical distinctions between artists usually called self-taught and those who people assume know what they’re doing, like Kara Walker or Matt Mullican. Separate histories were rejigged and shown to be reciprocal. The biggest such project was Massimiliano Gioni’s 2013 Venice Biennial, The Encyclopedic Palace, which also attempted a leveling and a mapping of influences in order to construct a nonsimplistic history. It’s impossible to avoid the novelty-discovery narrative, but these were comprehensive and conscious efforts that tinkered with the lingo (outliers? visionary?), because the lingo matters. Lots of lingo has been tried. Arthur Danto proposed to call them “artists sans phase.”4

After those and other landmark projects, you’d think: everyone understands how categories are both useful and exploitative, how contemporary art is an arbitrary genre that exists to reinforce power—and how OA reveals our deep desires to be free of the dictates of the market—valid!—while correlating what is great with what sells. But, as Adam Geczy puts it: “What makes the notion of the contemporary so challenging is that that it follows a dialectical model whose terms of reference are shifting.” The contemporary needs an imaginary outside.5

Today, the term is as broad as can be—it has to be, in order to counteract its essentializing and othering origins. The OA Fair website, which provides an excellent historical survey, offers the most generally helpful definition: “Dubuffet and Cardinal were writing primarily about extremely marginalized European artists: psychotics, mediums, and eccentrics. This has caused the common misconception that Outsider Art is essentially pathological, when in fact the central characteristic shared by Outsiders is simply their lack of conditioning by art history or art world trends.”

So what is it? Everyone who didn’t go to art school? Not so simple!

OUTSIDER ART FAIR 2025

This year’s Outsider Art Fair (OAF) in NYC was set up like any art fair, with galleries sponsoring booths full of wares in a giant brightly lit convention center. At least one booth seemed to be raising money for a nonprofit, but most function as typical dealerships.

The Times says that the OAF “can sometimes feel like a rock ‘n’ roll junk shop” but that this year’s was “more like an uptown antique store,” which are both true and tbh both accurate ways to describe different sections of Art Basel; the difference is that you can possibly afford something at this mall. (I’ll never forget an Armory edition where I heard a woman exclaim of Gagosian’s booth: “this is my favorite store!”) At OAF I heard a gallerist mention one work going for $40k; I saw several for under $500 (even seeing price tags at an art fair is weird). There were a lot of red stickers on the wall labels by the third day.

If you haven’t gone deep into the Outside you’ll be hard pressed to figure out why the art objects in the OAF belong in one room. You have mainstreamed Americana artists like Darger, Castle, and Traylor; you have the Euro-Art-Brut asylum artists like Adolf Wölfli and Heinrich Anton Müller; you have living artists currently making art who are neurodivergent, disabled, incarcerated, or otherwise identified as __; you have artifacts belonging to folk/craft traditions, often anonymous. One booth showed a beekeeping helmet that I could not figure out whether it was meant to be art, as well as a set of “African American chess pieces,” with no attribution. I guess the enduring lesson is that it’s art if you put it in an art fair, although there’s a lot to ask about how it got to the art fair. Some of the strangest and most remarkable things I saw were purses made by (mostly-anonymous) incarcerated people out of cigarette cartons.

For as long as I’ve been around, the only hard and fast rule about outsider art is that the artists do not have MFAs. But WAIT! At least one booth was showing millennials who seem Masterly educated and who live in urban cultural capitals! Their work looks sort of Outsidery I guess? I have no idea whether there’s some kind of qualification to entering into the fair (burden of Outsider Proof) or whether this is a good thing for an artist, but I’m sending some emails to try to find out. Do I care about this boundary or want to enforce it somehow? No!

Along those lines, however you theorize all of this, the OAF had the best art I’ve seen in ages, and if you ask me what “best” means I’ll be hard pressed to say something other than “sparks joy”—don’t make me say that unselfconscious genius really is a thing—but I’ll press myself a little and say these are aesthetic artifacts where, by dint of being thrown together, the art/craft, professional/amateur, and historical/contemporary distinctions are all overridden in favor of this stuff rules and this stuff sells. It is because Outsider Art is not a real category that the fair is full of amazing things that are fun to look at and difficult to place. And some stuff that, come on, is not art, but again, who cares. Well—unless you care about how the people got their hands on that stuff and what the artists want to be called and whether they are able to support themselves through the sale of their work. We’ve come full circle.

INCREDIBLE FIND

In my own personal discovery narrative at the fair, I now know about JUNE GUTMAN:

BUT THIS BLOG IS CALLED FAST WRITING??

This week that was not the case.

We definitely need nonboring autodidacts and we also need nonboring specialists who do know a lot about history and its weird loops. They are not going to overburden us with pretentiousness or academicize us to death if they’re good writers. It’s people who specialize in exactly the last two years of biennials that are boring.

Roger Cardinal, “In Quest of the Primitive,” Outsider Art, Praeger (1972).

Darby English, “Modernism’s War on Terror,” from the AMAZING catalog for the 2018 exhibition Outliers and American Vanguard Art at the National Gallery in 2018.

Geczy goes on: “The ‘art world’ is too much of a disordered, discordant mass to have an inside let alone an outside....In short, there have always been outsides to art, and these outsides are multiple and exist according to many categories; so to stake a claim for a principle outside is either simplistic or carries the ignorance of arrogance.”

Adam Geczy, “The Sordid Fraud of Outsider Art,” Contemporary Art+Culture, Volume 39.1: March 2010.

Yes to the (Eat, Pray, Love) research trip. If only we could be honest about this in grant applications

What a fascinating post! Thank you. Not sure if this is relevant, but this really overturned the binary for me, back in 2006 (aargh): https://artmap.com/whitechapel/exhibition/inner-worlds-outside-2006.